|

|

@@ -13,9 +13,9 @@ Una buena manera de organizar y estructurar los programas de computadoras es div

|

|

13

|

13

|

Haz visto que todos los programas en C++ deben contener la función `main` que es donde comienza el programa. Probablemente ya haz utilizado funciones como `pow`, `sin`, `cos` o `sqrt` de la biblioteca de matemática `cmath`. Dado que en casi todas las experiencias de laboratorio futuras estarás utilizando funciones que ya han sido creadas, necesitas aprender cómo trabajar con ellas. Más adelante aprenderás cómo diseñarlas y validarlas. En esta experiencia de laboratorio invocarás y definirás funciones que calculan las coordenadas de los puntos de las gráficas de algunas curvas. También practicarás la implementación de expresiones aritméticas en C++.

|

|

14

|

14

|

|

|

15

|

15

|

|

|

16

|

|

-##Objetivos:

|

|

|

16

|

+## Objetivos:

|

|

17

|

17

|

|

|

18

|

|

-1. Identificar las partes de una función: tipo, nombre, lista de parámetros y cuerpo de la función.

|

|

|

18

|

+1. Identificar las partes de una función: tipo, nombre, lista de parámetros y cuerpo de la función.

|

|

19

|

19

|

2. Invocar funciones ya creadas enviando argumentos por valor ("pass by value") y por referencia ("pass by reference").

|

|

20

|

20

|

3. Implementar una función sobrecargada simple.

|

|

21

|

21

|

4. Implementar funciones simples que utilicen parámetros por referencia.

|

|

|

@@ -23,7 +23,7 @@ Haz visto que todos los programas en C++ deben contener la función `main` que e

|

|

23

|

23

|

|

|

24

|

24

|

|

|

25

|

25

|

|

|

26

|

|

-##Pre-Lab:

|

|

|

26

|

+## Pre-Lab:

|

|

27

|

27

|

|

|

28

|

28

|

Antes de llegar al laboratorio debes:

|

|

29

|

29

|

|

|

|

@@ -35,7 +35,7 @@ Antes de llegar al laboratorio debes:

|

|

35

|

35

|

|

|

36

|

36

|

c. la diferencia entre parámetros pasados por valor y por referencia.

|

|

37

|

37

|

|

|

38

|

|

- d. como devolver el resultado de una función.

|

|

|

38

|

+ d. cómo devolver el resultado de una función.

|

|

39

|

39

|

|

|

40

|

40

|

e. implementar expresiones aritméticas en C++.

|

|

41

|

41

|

|

|

|

@@ -53,19 +53,18 @@ Antes de llegar al laboratorio debes:

|

|

53

|

53

|

---

|

|

54

|

54

|

|

|

55

|

55

|

|

|

56

|

|

-##Funciones

|

|

57

|

|

-

|

|

|

56

|

+## Funciones

|

|

58

|

57

|

|

|

59

|

58

|

En matemática, una función $f$ es una regla que se usa para asignar a cada elemento $x$ de un conjunto que se llama *dominio*, uno (y solo un) elemento $y$ de un conjunto que se llama *campo de valores*. Por lo general, esa regla se representa como una ecuación, $y=f(x)$. La variable $x$ es el parámetro de la función y la variable $y$ contendrá el resultado de la función. Una función puede tener más de un parámetro pero solo un resultado. Por ejemplo, una función puede tener la forma $y=f(x_1,x_2)$ en donde hay dos parámetros y para cada par $(a,b)$ que se use como argumento de la función, la función tiene un solo valor de $y=f(a,b)$. El dominio de la función te dice el tipo de valor que debe tener el parámetro y el campo de valores el tipo de valor que tendrá el resultado que devuelve la función.

|

|

60

|

59

|

|

|

61

|

|

-Las funciones en lenguajes de programación de computadoras son similares. Una función

|

|

|

60

|

+Las funciones en lenguajes de programación de computadoras son similares. Una función

|

|

62

|

61

|

tiene una serie de instrucciones que toman los valores asignados a los parámetros y realiza alguna tarea. En C++ y en algunos otros lenguajes de programación, las funciones solo pueden devolver un resultado, tal y como sucede en matemáticas. La única diferencia es que una función en programación puede que no devuelva valor (en este caso la función se declara `void`). Si la función va a devolver algún valor, se hace con la instrucción `return`. Al igual que en matemática tienes que especificar el dominio y el campo de valores, en programación tienes que especificar los tipos de valores que tienen los parámetros y el resultado que devuelve la función; esto lo haces al declarar la función.

|

|

63

|

62

|

|

|

64

|

|

-###Encabezado de una función:

|

|

|

63

|

+### Encabezado de una función:

|

|

65

|

64

|

|

|

66

|

65

|

La primera oración de una función se llama el *encabezado* y su estructura es como sigue:

|

|

67

|

66

|

|

|

68

|

|

-`tipo nombre(tipo parámetro01, ..., tipo parámetro0n)`

|

|

|

67

|

+`tipo nombre(tipo parámetro_1, ..., tipo parámetro_n)`

|

|

69

|

68

|

|

|

70

|

69

|

Por ejemplo,

|

|

71

|

70

|

|

|

|

@@ -73,7 +72,7 @@ Por ejemplo,

|

|

73

|

72

|

|

|

74

|

73

|

sería el encabezado de la función llamada `ejemplo`, que devuelve un valor entero. La función recibe como argumentos un valor entero (y guardará una copia en `var1`), un valor de tipo `float` (y guardará una copia en `var2`) y la referencia a una variable de tipo `char` que se guardará en la variable de referencia `var3`. Nota que `var3` tiene el signo `&` antes del nombre de la variable. Esto indica que `var3` contendrá la referencia a un caracter.

|

|

75

|

74

|

|

|

76

|

|

-###Invocación

|

|

|

75

|

+### Invocación

|

|

77

|

76

|

|

|

78

|

77

|

Si queremos guardar el valor del resultado de la función `ejemplo` en la variable `resultado` (que deberá ser de tipo entero), invocamos la función pasando argumentos de manera similar a:

|

|

79

|

78

|

|

|

|

@@ -92,8 +91,9 @@ o utilizarlo en una expresión aritmética:

|

|

92

|

91

|

|

|

93

|

92

|

|

|

94

|

93

|

|

|

95

|

|

-###Funciones sobrecargadas (‘overloaded’)

|

|

96

|

|

-Las funciones sobrecargadas son funciones que poseen el mismo nombre, pero *firma* diferente.

|

|

|

94

|

+### Funciones sobrecargadas (‘overloaded’)

|

|

|

95

|

+

|

|

|

96

|

+Las funciones sobrecargadas son funciones que poseen el mismo nombre, pero tienen *firmas* diferentes.

|

|

97

|

97

|

|

|

98

|

98

|

La firma de una función se compone del nombre de la función, y los tipos de parámetros que recibe, pero no incluye el tipo que devuelve.

|

|

99

|

99

|

|

|

|

@@ -101,7 +101,7 @@ Los siguientes prototipos de funciones tienen la misma firma:

|

|

101

|

101

|

|

|

102

|

102

|

```

|

|

103

|

103

|

int ejemplo(int, int) ;

|

|

104

|

|

-void ejemplo(int, int) ;

|

|

|

104

|

+void ejemplo(int, int) ;

|

|

105

|

105

|

string ejemplo(int, int) ;

|

|

106

|

106

|

```

|

|

107

|

107

|

|

|

|

@@ -132,26 +132,26 @@ En este último ejemplo la función ejemplo es sobrecargada ya que hay 5 funcion

|

|

132

|

132

|

|

|

133

|

133

|

|

|

134

|

134

|

|

|

135

|

|

-###Valores por defecto

|

|

|

135

|

+### Valores por defecto

|

|

136

|

136

|

|

|

137

|

137

|

Se pueden asignar valores por defecto ("default") a los parámetros de las funciones comenzando desde el parámetro más a la derecha. No hay que inicializar todos los parámetros pero los que se inicializan deben ser consecutivos: no se puede dejar parámetros sin inicializar entre dos parámetros que estén inicializados. Esto permite la invocación de la función sin tener que enviar los valores en las posiciones que corresponden a parámetros inicializados.

|

|

138

|

138

|

|

|

139

|

139

|

**Ejemplos de encabezados de funciones e invocaciones válidas:**

|

|

140

|

140

|

|

|

141

|

|

-1. **Encabezado:** `int ejemplo(int var1, float var2, int var3 = 10)` Aquí se inicializa `var3` a 10.

|

|

|

141

|

+1. **Encabezado:** `int ejemplo(int var1, float var2, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

142

|

142

|

|

|

143

|

|

- **Invocaciones:**

|

|

|

143

|

+ **Invocaciones:**

|

|

144

|

144

|

|

|

145

|

|

- a. `ejemplo(5, 3.3, 12)` Esta invocación asigna el valor 5 a `var1`, el valor 3.3 a `var2`, y el valor 12 a `var3`.

|

|

|

145

|

+ a. `ejemplo(5, 3.3, 12)` Esta invocación asigna el valor 5 a `var1`, el valor 3.3 a `var2`, y el valor 12 a `var3`.

|

|

146

|

146

|

|

|

147

|

147

|

b. `ejemplo(5, 3.3)` Esta invocación envía valores para los primeros dos parámetros y el valor del último parámetro será el valor por defecto asignado en el encabezado. Esto es, los valores de las variables en la función serán: `var1` tendrá 5, `var2` tendrá 3.3, y `var3` tendrá 10.

|

|

148

|

148

|

|

|

149

|

149

|

|

|

150

|

|

-2. **Encabezado:** `int ejemplo(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)` Aquí se inicializa `var2` a 5 y `var3` a 10.

|

|

151

|

|

-

|

|

152

|

|

- **Invocaciones:**

|

|

|

150

|

+2. **Encabezado:** `int ejemplo(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

|

151

|

+

|

|

|

152

|

+ **Invocaciones:**

|

|

153

|

153

|

|

|

154

|

|

- a. `ejemplo(5, 3.3, 12)` Esta invocación asigna el valor 5 a `var1`, el valor 3.3 a `var2`, y el valor 12 a `var3`.

|

|

|

154

|

+ a. `ejemplo(5, 3.3, 12)` Esta invocación asigna el valor 5 a `var1`, el valor 3.3 a `var2`, y el valor 12 a `var3`.

|

|

155

|

155

|

|

|

156

|

156

|

b. `ejemplo(5, 3.3)` En esta invocación solo se envían valores para los primeros dos parámetros, y el valor del último parámetro es el valor por defecto. Esto es, el valor de `var1` dentro de la función será 5, el de `var2` será 3.3 y el de `var3` será 10.

|

|

157

|

157

|

|

|

|

@@ -159,11 +159,11 @@ Se pueden asignar valores por defecto ("default") a los parámetros de las funci

|

|

159

|

159

|

|

|

160

|

160

|

**Ejemplo de un encabezado de funciones válido con invocaciones inválidas:**

|

|

161

|

161

|

|

|

162

|

|

-1. **Encabezado:** `int ejemplo(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

|

162

|

+1. **Encabezado:** `int ejemplo(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

163

|

163

|

|

|

164

|

|

- **Invocación:**

|

|

|

164

|

+ **Invocación:**

|

|

165

|

165

|

|

|

166

|

|

- a. `ejemplo(5, ,10)` Esta invocación es **inválida** porque deja espacio vacío en el argumento del medio.

|

|

|

166

|

+ a. `ejemplo(5, ,10)` Esta invocación es **inválida** porque deja espacio vacío en el argumento del medio.

|

|

167

|

167

|

|

|

168

|

168

|

b. `ejemplo()` Esta invocación es **inválida** ya que `var1` no estaba inicializada y no recibe ningún valor en la invocación.

|

|

169

|

169

|

|

|

|

@@ -179,9 +179,9 @@ Se pueden asignar valores por defecto ("default") a los parámetros de las funci

|

|

179

|

179

|

|

|

180

|

180

|

---

|

|

181

|

181

|

|

|

182

|

|

-##Ecuaciones paramétricas

|

|

|

182

|

+## Ecuaciones paramétricas

|

|

183

|

183

|

|

|

184

|

|

-Las *ecuaciones paramétricas* nos permiten representar una cantidad como función de una o más variables independientes llamadas *parámetros*. En muchas ocasiones resulta útil representar curvas utilizando un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas que expresen las coordenadas de los puntos de la curva como funciones de los parámetros. Por ejemplo, en tu curso de trigonometría debes haber estudiado que la ecuación de un círculo con radio $r$ y centro en el origen tiene una forma así:

|

|

|

184

|

+Las *ecuaciones paramétricas* nos permiten representar una cantidad como función de una o más variables independientes llamadas *parámetros*. En muchas ocasiones resulta útil representar curvas utilizando un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas que expresen las coordenadas de los puntos de la curva como funciones de los parámetros. Por ejemplo, en tu curso de trigonometría debes haber estudiado que la ecuación de un círculo con radio $r$ y centro en el origen tiene una forma así:

|

|

185

|

185

|

|

|

186

|

186

|

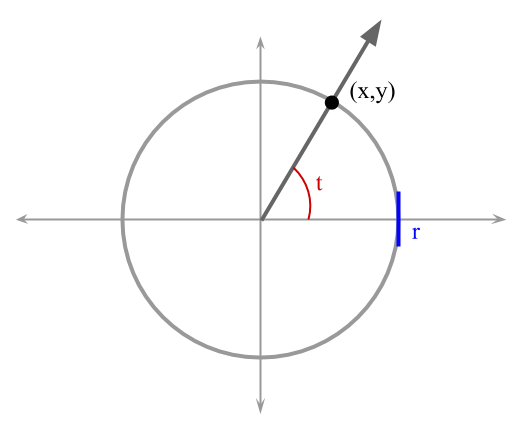

$$x^2+y^2=r^2.$$

|

|

187

|

187

|

|

|

|

@@ -190,7 +190,7 @@ Los puntos $(x,y)$ que satisfacen esta ecuación son los puntos que forman el c

|

|

190

|

190

|

|

|

191

|

191

|

$$x^2+y^2=4,$$

|

|

192

|

192

|

|

|

193

|

|

-y sus puntos son los pares ordenados $(x,y)$ que satisfacen esa ecuación. Una forma paramétrica de expresar las coordenadas de los puntos del círculo con radio $r$ y centro en el origen es:

|

|

|

193

|

+y sus puntos son los pares ordenados $(x,y)$ que satisfacen esa ecuación. Una forma paramétrica de expresar las coordenadas de los puntos del círculo con radio $r$ y centro en el origen es:

|

|

194

|

194

|

|

|

195

|

195

|

$$x=r \cos(t)$$

|

|

196

|

196

|

|

|

|

@@ -201,41 +201,38 @@ donde $t$ es un parámetro que corresponde a la medida (en radianes) del ángulo

|

|

201

|

201

|

|

|

202

|

202

|

---

|

|

203

|

203

|

|

|

204

|

|

-

|

|

|

204

|

+

|

|

205

|

205

|

|

|

206

|

|

-<b>Figura 1.</b> Círculo con centro en el origen y radio $r$.

|

|

|

206

|

+**Figura 1.** Círculo con centro en el origen y radio $r$.

|

|

207

|

207

|

|

|

208

|

208

|

|

|

209

|

209

|

---

|

|

210

|

210

|

|

|

211

|

|

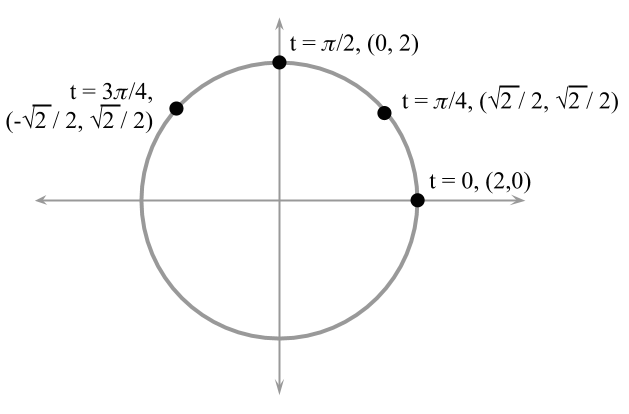

-Para graficar una curva que está definida usando ecuaciones paramétricas, computamos los valores de $x$ y $y$ para un conjunto de valores del parámetro. Por ejemplo, para $r = 2$, algunos de los valores son

|

|

|

211

|

+Para graficar una curva que está definida usando ecuaciones paramétricas, computamos los valores de $x$ y $y$ para un conjunto de valores del parámetro. Por ejemplo, la Figura 2 resalta los valores de $t$, $x$ y $y$ para el círculo con $r = 2$.

|

|

212

|

212

|

|

|

213

|

213

|

---

|

|

214

|

214

|

|

|

215

|

|

-| $t$ | $x$ | $y$ |

|

|

216

|

|

-|-----|-----|-----|

|

|

217

|

|

-| $0$ | $2$ | $0$ |

|

|

218

|

|

-| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$ | $\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$ |

|

|

219

|

|

-| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $0$ | $2$ |

|

|

220

|

215

|

|

|

221

|

216

|

|

|

|

217

|

+

|

|

|

218

|

+

|

|

222

|

219

|

**Figura 2.** Algunas coordenadas de los puntos $(x,y)$ del círculo con radio $r=2$ y centro en el origen.

|

|

223

|

220

|

|

|

224

|

221

|

---

|

|

225

|

222

|

|

|

226

|

223

|

---

|

|

227

|

224

|

|

|

228

|

|

-##Sesión de laboratorio:

|

|

|

225

|

+## Sesión de laboratorio:

|

|

229

|

226

|

|

|

230

|

|

-En la introducción al tema de funciones viste que, tanto en matemáticas como en algunos lenguajes de programación, una función no puede devolver más de un resultado. En los ejercicios de esta experiencia de laboratorio practicarás cómo usar variables de referencia para poder obtener varios resultados de una función.

|

|

|

227

|

+En la introducción al tema de funciones viste que, tanto en matemáticas como en algunos lenguajes de programación, una función no puede devolver más de un resultado. En los ejercicios de esta experiencia de laboratorio practicarás cómo usar variables de referencia para poder obtener varios resultados de una función.

|

|

231

|

228

|

|

|

232

|

|

-###Ejercicio 1

|

|

|

229

|

+### Ejercicio 1

|

|

233

|

230

|

|

|

234

|

231

|

En este ejercicio estudiarás la diferencia entre pase por valor y pase por referencia.

|

|

235

|

232

|

|

|

236

|

233

|

**Instrucciones**

|

|

237

|

234

|

|

|

238

|

|

-1. Carga a Qt el proyecto `prettyPlot` haciendo doble "click" en el archivo `prettyPlot.pro` que se encuentra en la carpeta `Documents/eip/Functions-PrettyPlots` de tu computadora. También puedes ir a `http://bitbucket.org/eip-uprrp/functions-prettyplots` para descargar la carpeta `Functions-PrettyPlots` a tu computadora.

|

|

|

235

|

+1. Carga a Qt Creator el proyecto `prettyPlot` haciendo doble "click" en el archivo `prettyPlot.pro` que se encuentra en la carpeta `Documents/eip/Functions-PrettyPlots` de tu computadora. También puedes ir a `http://bitbucket.org/eip-uprrp/functions-prettyplots` para descargar la carpeta `Functions-PrettyPlots` a tu computadora.

|

|

239

|

236

|

|

|

240

|

237

|

2. Configura el proyecto y ejecuta el programa marcando la flecha verde en el menú de la izquierda de la ventana de Qt Creator. El programa debe mostrar una ventana parecida a la Figura 3.

|

|

241

|

238

|

|

|

|

@@ -244,22 +241,53 @@ En este ejercicio estudiarás la diferencia entre pase por valor y pase por refe

|

|

244

|

241

|

|

|

245

|

242

|

|

|

246

|

243

|

**Figura 3.** Gráfica de un círculo de radio 5 y centro en el origen desplegada por el programa *PrettyPlot*.

|

|

247

|

|

-

|

|

248

|

|

- ---

|

|

249

|

244

|

|

|

|

245

|

+ ---

|

|

250

|

246

|

|

|

251

|

247

|

3. Abre el archivo `main.cpp` (en Sources). Estudia la función `illustration` y su invocación desde la función `main`. Nota que las variables `argValue` y `argRef` están inicializadas a 0 y que la invocación a `illustration` hace un pase por valor de `argValue` y un pase por referencia de `argRef`. Nota también que a los parámetros correspondientes en `illustration` se les asigna el valor 1.

|

|

252

|

248

|

|

|

|

249

|

+ void illustration(int paramValue, int ¶mRef) {

|

|

|

250

|

+ paramValue = 1;

|

|

|

251

|

+ paramRef = 1;

|

|

|

252

|

+ cout << endl << "The content of paramValue is: " << paramValue << endl

|

|

|

253

|

+ << "The content of paramRef is: " << paramRef << endl;

|

|

|

254

|

+ }

|

|

|

255

|

+

|

|

253

|

256

|

4. Ejecuta el programa y observa lo que se despliega en la ventana `Application Output`. Nota la diferencia entre el contenido las variables `argValue` y `argRef` a pesar de que ambas tenían el mismo valor inicial y de que a `paramValue` y `paramRef` se les asignó el mismo valor. Explica por qué el contenido de `argValor` no cambia, mientras que el contenido de `argRef` cambia de 0 a 1.

|

|

254

|

257

|

|

|

255

|

|

-###Ejercicio 2

|

|

|

258

|

+### Ejercicio 2

|

|

256

|

259

|

|

|

257

|

260

|

En este ejercicio practicarás la creación de una función sobrecargada.

|

|

258

|

261

|

|

|

259

|

262

|

**Instrucciones**

|

|

260

|

263

|

|

|

261

|

|

-1. Estudia el código de la función `main()` del archivo `main.cpp`. La línea `XYPlotWindow wCircleR5;` crea el objeto `wCircleR5` que será la ventana en donde se dibujará una gráfica, en este caso la gráfica de un círculo de radio 5. De manera similar se crean los objetos `wCircle` y `wButterfly`. Observa el ciclo `for`. En este ciclo se genera una serie de valores para el ángulo $t$ y se invoca la función `circle`, pasándole el valor de $t$ y las referencias a $x$ y $y$. La función `circle` no devuelve valor pero, usando parámetros por referencia, calcula valores para las coordenadas $xCoord$ y $yCoord$ del círculo con centro en el origen y radio 5 y permite que la función `main` tenga esos valores en las variables `x` , `y`.

|

|

|

264

|

+1. Estudia el código de la función `main()` del archivo `main.cpp`. La línea `XYPlotWindow wCircleR5;` crea el objeto `wCircleR5` que será la ventana en donde se dibujará una gráfica, en este caso la gráfica de un círculo de radio 5. De manera similar se crean los objetos `wCircle` y `wButterfly`. Observa el ciclo `for`. En este ciclo se genera una serie de valores para el ángulo $t$ y se invoca la función `circle`, pasándole el valor de $t$ y las referencias a $x$ y $y$. La función `circle` no devuelve valor pero, usando parámetros por referencia, calcula valores para las coordenadas $xCoord$ y $yCoord$ del círculo con centro en el origen y radio 5 y permite que la función `main` tenga esos valores en las variables `x` , `y`.

|

|

|

265

|

+

|

|

|

266

|

+ XYPlotWindow wCircleR5;

|

|

|

267

|

+ XYPlotWindow wCircle;

|

|

|

268

|

+ XYPlotWindow wButterfly;

|

|

|

269

|

+

|

|

|

270

|

+ double r;

|

|

|

271

|

+ double y = 0.00;

|

|

|

272

|

+ double x = 0.00;

|

|

|

273

|

+ double increment = 0.01;

|

|

|

274

|

+ int argValue=0, argRef=0;

|

|

|

275

|

+

|

|

|

276

|

+ // invoke the function illustration to view the contents of variables

|

|

|

277

|

+ // by value and by reference

|

|

262

|

278

|

|

|

|

279

|

+ illustration(argValue,argRef);

|

|

|

280

|

+ cout << endl << "The content of argValue is: " << argValue << endl

|

|

|

281

|

+ << "The content of argRef is: " << argRef << endl;

|

|

|

282

|

+

|

|

|

283

|

+ // repeat for several values of the angle t

|

|

|

284

|

+ for (double t = 0; t < 16*M_PI; t = t + increment) {

|

|

|

285

|

+

|

|

|

286

|

+ // invoke circle with the angle t and reference variables x, y as arguments

|

|

|

287

|

+ circle(t,x,y);

|

|

|

288

|

+

|

|

|

289

|

+ // add the point (x,y) to the graph of the circle

|

|

|

290

|

+ wCircleR5.AddPointToGraph(x,y);

|

|

263

|

291

|

|

|

264

|

292

|

Luego de la invocación, cada par ordenado $(x,y)$ es añadido a la gráfica del círculo por el método `AddPointToGraph(x,y)`. Luego del ciclo se invoca el método `Plot()`, que "dibuja" los puntos, y el método `show()`, que muestra la gráfica. Los *métodos* son funciones que nos permiten trabajar con los datos de los objetos. Nota que cada uno de los métodos se escribe luego de `wCircleR5`, seguido de un punto. En una experiencia de laboratorio posterior aprenderás más sobre objetos y practicarás cómo crearlos e invocar sus métodos.

|

|

265

|

293

|

|

|

|

@@ -267,7 +295,7 @@ En este ejercicio practicarás la creación de una función sobrecargada.

|

|

267

|

295

|

|

|

268

|

296

|

2. Ahora crearás una función sobrecargada `circle` que reciba como argumentos el valor del ángulo $t$, la referencia a las variables $x$ y $y$, y el valor para el radio del círculo. Invoca desde `main()` la función sobrecargada `circle` que acabas de implementar para calcular los valores de las coordenadas $x$ y $y$ del círculo con radio 15 y dibujar su gráfica. Grafica el círculo dentro del objeto `wCircle`. Para esto, debes invocar desde `main()` los métodos `AddPointToGraph(x,y)`, `Plot` y `show`. Recuerda que éstos deben ser precedidos por `wCircle`, por ejemplo, `wCircle.show()`.

|

|

269

|

297

|

|

|

270

|

|

-###Ejercicio 3

|

|

|

298

|

+### Ejercicio 3

|

|

271

|

299

|

|

|

272

|

300

|

En este ejercicio implantarás otra función para calcular las coordenadas de los puntos de la gráfica de una curva.

|

|

273

|

301

|

|

|

|

@@ -275,29 +303,28 @@ En este ejercicio implantarás otra función para calcular las coordenadas de lo

|

|

275

|

303

|

|

|

276

|

304

|

1. Ahora crearás una función para calcular las coordenadas de los puntos de la gráfica que parece una mariposa. Las ecuaciones paramétricas para las coordenadas de los puntos de la gráfica están dadas por:

|

|

277

|

305

|

|

|

278

|

|

-

|

|

279

|

|

-

|

|

280

|

306

|

$$x=5\cos(t) \left[ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t) \right]$$

|

|

281

|

|

- $$y= 10\sin(t) \left[ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t) \right].$$

|

|

282

|

307

|

|

|

|

308

|

+ $$y= 10\sin(t) \left[ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t) \right].$$

|

|

283

|

309

|

|

|

284

|

310

|

Observa que ambas expresiones son casi iguales, excepto que una comienza con $5\cos(t)$ y la otra con $10\sin(t)$. En lugar de realizar el cómputo de $ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t)$ dos veces, puedes asignar su valor a otra variable $q$ y realizar el cómputo así:

|

|

285

|

311

|

|

|

286

|

312

|

$$q = \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t)$$

|

|

|

313

|

+

|

|

287

|

314

|

$$x = 5 \cos(t)(q)$$

|

|

|

315

|

+

|

|

288

|

316

|

$$y = 10 \sin(t)(q).$$

|

|

289

|

317

|

|

|

290

|

|

-

|

|

291

|

318

|

2. Implementa la función `butterfly` utilizando las expresiones de arriba, invoca la función desde `main()` y observa la gráfica que resulta. Se supone que parezca una mariposa. Esta gráfica debe haber sido obtenida dentro de un objeto `XYPlotWindow` llamado `wButterfly`, invocando métodos de manera similar a como hiciste en el Ejercicio 2 para el círculo.

|

|

292

|

319

|

|

|

293

|

|

-En [3] puedes encontrar otras ecuaciones paramétricas de otras curvas interesantes.

|

|

|

320

|

+En [2] y [3] puedes encontrar otras ecuaciones paramétricas de otras curvas interesantes.

|

|

294

|

321

|

|

|

295

|

322

|

|

|

296

|

323

|

---

|

|

297

|

324

|

|

|

298

|

325

|

---

|

|

299

|

326

|

|

|

300

|

|

-##Entregas

|

|

|

327

|

+## Entregas

|

|

301

|

328

|

|

|

302

|

329

|

Utiliza "Entrega" en Moodle para entregar el archivo `main.cpp` que contiene las funciones que implementaste, las invocaciones y cambios que hiciste en los ejercicios 2 y 3. Recuerda utilizar buenas prácticas de programación, incluir el nombre de los programadores y documentar tu programa.

|

|

303

|

330

|

|

|

|

@@ -336,15 +363,15 @@ A good way to organize and structure computer programs is dividing them into sma

|

|

336

|

363

|

You've seen that all programs written in C++ must contain the `main` function where the program begins. You've probably already used functions such as `pow`, `sin`, `cos`, or `sqrt` from the `cmath` library. Since in almost all of the upcoming lab activities you will continue using pre-defined functions, you need to understand how to work with them. In future exercises you will learn how to design and validate functions. In this laboratory experience you will invoke and define functions that compute the coordinates of the points of the graphs of some curves. You will also practice the implementation of arithmetic expressions in C++.

|

|

337

|

364

|

|

|

338

|

365

|

|

|

339

|

|

-##Objectives:

|

|

|

366

|

+## Objectives:

|

|

340

|

367

|

|

|

341

|

|

-1. Identify the parts of a function: return type, name, list of parameters, and body.

|

|

342

|

|

-2. Invoke pre-defined functions by passing arguments by value ("pass by value"), and by reference ("pass by reference").

|

|

|

368

|

+1. Identify the parts of a function: return type, name, list of parameters, and body.

|

|

|

369

|

+2. Invoke pre-defined functions by passing arguments by value ("pass by value"), and by reference ("pass by reference").

|

|

343

|

370

|

3. Implement a simple overloaded function.

|

|

344

|

371

|

4. Implement a simple function that utilizes parameters by reference.

|

|

345

|

372

|

5. Implement arithmetic expressions in C++.

|

|

346

|

373

|

|

|

347

|

|

-##Pre-Lab:

|

|

|

374

|

+## Pre-Lab:

|

|

348

|

375

|

|

|

349

|

376

|

Before you get to the laboratory you should have:

|

|

350

|

377

|

|

|

|

@@ -372,17 +399,17 @@ Before you get to the laboratory you should have:

|

|

372

|

399

|

|

|

373

|

400

|

---

|

|

374

|

401

|

|

|

375

|

|

-##Functions

|

|

|

402

|

+## Functions

|

|

376

|

403

|

|

|

377

|

404

|

In mathematics, a function $f$ is a rule that is used to assign to each element $x$ from a set called *domain*, one (and only one) element $y$ from a set called *range*. This rule is commonly represented with an equation, $y=f(x)$. The variable $x$ is the parameter of the function and the variable $y$ will contain the result of the function. A function can have more than one parameter, but only one result. For example, a function can have the form $y=f(x_1,x_2)$ where there are two parameters, and for each pair $(a,b)$ that is used as an argument in the function, the function has only one value of $y=f(a,b)$. The domain of the function tells us the type of value that the parameter should have and the range tells us the value that the returned result will have.

|

|

378

|

405

|

|

|

379

|

406

|

Functions in programming languages are similar. A function has a series of instructions that take the assigned values as parameters and performs a certain task. In C++ and other programming languages, functions return only one result, as it happens in mathematics. The only difference is that a *programming* function could possibly not return any value (in this case the function is declared as `void`). If the function will return a value, we use the instruction `return`. As in math, you need to specify the types of values that the function's parameters and result will have; this is done when declaring the function.

|

|

380

|

407

|

|

|

381

|

|

-###Function header:

|

|

|

408

|

+### Function header:

|

|

382

|

409

|

|

|

383

|

410

|

The first sentence of a function is called the *header* and its structure is as follows:

|

|

384

|

411

|

|

|

385

|

|

-`type name(type parameter01, ..., type parameter0n)`

|

|

|

412

|

+`type name(type parameter_1, ..., type parameter_n)`

|

|

386

|

413

|

|

|

387

|

414

|

For example,

|

|

388

|

415

|

|

|

|

@@ -391,7 +418,7 @@ For example,

|

|

391

|

418

|

would be the header of the function called `example`, which returns an integer value. The function receives as arguments an integer value (and will store a copy in `var1`), a value of type `float` (and will store a copy in `var2`) and the reference to a variable of type `char` that will be stored in the reference variable `var3`. Note that `var3` has a & symbol before the name of the variable. This indicates that `var3` will contain the reference to a character.

|

|

392

|

419

|

|

|

393

|

420

|

|

|

394

|

|

-###Invoking

|

|

|

421

|

+### Invoking

|

|

395

|

422

|

|

|

396

|

423

|

|

|

397

|

424

|

If we want to store the value of the `example` function's result in a variable `result` (that would be of type integer), we invoke the function by passing arguments as follows:

|

|

|

@@ -410,9 +437,7 @@ or use it in an arithmetic expression:

|

|

410

|

437

|

|

|

411

|

438

|

|

|

412

|

439

|

|

|

413

|

|

-

|

|

414

|

|

-

|

|

415

|

|

-###Overloaded functions

|

|

|

440

|

+### Overloaded functions

|

|

416

|

441

|

|

|

417

|

442

|

Overloaded functions are functions that have the same name, but a different *signature*.

|

|

418

|

443

|

|

|

|

@@ -422,7 +447,7 @@ The following function prototypes have the same signature:

|

|

422

|

447

|

|

|

423

|

448

|

```

|

|

424

|

449

|

int example(int, int) ;

|

|

425

|

|

-void example(int, int) ;

|

|

|

450

|

+void example(int, int) ;

|

|

426

|

451

|

string example(int, int) ;

|

|

427

|

452

|

```

|

|

428

|

453

|

|

|

|

@@ -454,13 +479,13 @@ In that last example, the function `example` is overloaded since there are 5 fun

|

|

454

|

479

|

|

|

455

|

480

|

|

|

456

|

481

|

|

|

457

|

|

-###Values by default

|

|

|

482

|

+### Values by default

|

|

458

|

483

|

|

|

459

|

484

|

Values by default can be assigned to the parameters of the functions starting from the first parameter to the right. It is not necessary to initialize all of the parameters, but the ones that are initialized should be consecutive: parameters in between two parameters cannot be left uninitialized. This allows calling the function without having to send values in the positions that correspond to the initialized parameters.

|

|

460

|

485

|

|

|

461

|

486

|

**Examples of function headers and valid invocations:**

|

|

462

|

487

|

|

|

463

|

|

-1. **Headers:** `int example(int var1, float var2, int var3 = 10)` Here `var3` is initialized to 10.

|

|

|

488

|

+1. **Headers:** `int example(int var1, float var2, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

464

|

489

|

|

|

465

|

490

|

**Invocations:**

|

|

466

|

491

|

|

|

|

@@ -469,11 +494,9 @@ Values by default can be assigned to the parameters of the functions starting fr

|

|

469

|

494

|

b. `example(5, 3.3)` This function call sends the values for the first two parameters and the value for the last parameter will be the value assigned by default in the header. That is, the values in the variables in the function will be as follows: `var1` will be 5, `var2` will be 3.3, and `var3` will be 10.

|

|

470

|

495

|

|

|

471

|

496

|

2. **Header:** `int example(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

472

|

|

-Here `var2` is initialized to 5 and `var3` to 10.

|

|

473

|

497

|

|

|

474

|

498

|

**Invocations:**

|

|

475

|

499

|

|

|

476

|

|

-

|

|

477

|

500

|

a. `example(5, 3.3, 12)` This function call assigns the value 5 to `var1`, the value 3.3 to `var2`, and the value 12 to `var3`.

|

|

478

|

501

|

|

|

479

|

502

|

b. `example(5, 3.3)` In this function call only the first two parameters are given values, and the value for the last parameter is the value by default. That is, the value for `var1` within the function will be 5, that of `var2` will be 3.3, and `var3` will be 10.

|

|

|

@@ -482,14 +505,14 @@ Here `var2` is initialized to 5 and `var3` to 10.

|

|

482

|

505

|

|

|

483

|

506

|

|

|

484

|

507

|

**Example of a valid function header with invalid invocations:**

|

|

485

|

|

-1. **Header:** `int example(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

486

|

508

|

|

|

|

509

|

+1. **Header:** `int example(int var1, float var2=5.0, int var3 = 10)`

|

|

487

|

510

|

|

|

488

|

511

|

**Invocation:**

|

|

489

|

512

|

|

|

490

|

513

|

a. `example(5, , 10)` This function call is **invalid** because it leaves an empty space in the middle argument.

|

|

491

|

514

|

|

|

492

|

|

- b. `example()` This function call is **invalid** because `var1` was not assigned a default value. A valid invocation to the function `example` needs at least one argument (the first).

|

|

|

515

|

+ b. `example()` This function call is **invalid** because `var1` was not assigned a default value. A valid invocation to the function `example` needs at least one argument (the first).

|

|

493

|

516

|

|

|

494

|

517

|

|

|

495

|

518

|

**Examples of invalid function headers:**

|

|

|

@@ -527,9 +550,9 @@ where $t$ is a parameter that corresponds to the measure (in radians) of the pos

|

|

527

|

550

|

|

|

528

|

551

|

---

|

|

529

|

552

|

|

|

530

|

|

-

|

|

|

553

|

+

|

|

531

|

554

|

|

|

532

|

|

-<b>Figure 1.</b> Circle with center in the origin and radius $r$.

|

|

|

555

|

+**Figure 1.** Circle with center in the origin and radius $r$.

|

|

533

|

556

|

|

|

534

|

557

|

|

|

535

|

558

|

---

|

|

|

@@ -539,12 +562,7 @@ To plot a curve that is described by parametric equations, we compute the $x$ a

|

|

539

|

562

|

|

|

540

|

563

|

---

|

|

541

|

564

|

|

|

542

|

|

-| $t$ | $x$ | $y$ |

|

|

543

|

|

-|-----|-----|-----|

|

|

544

|

|

-| $0$ | $2$ | $0$ |

|

|

545

|

|

-| $\frac{\pi}{4}$ | $\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$ | $\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$ |

|

|

546

|

|

-| $\frac{\pi}{2}$ | $0$ | $2$ |

|

|

547

|

|

-

|

|

|

565

|

+

|

|

548

|

566

|

|

|

549

|

567

|

**Figure 2.** Some coordinates for the points $(x,y)$ for the circle with radius $r=2$ and center in the origin.

|

|

550

|

568

|

|

|

|

@@ -552,11 +570,11 @@ To plot a curve that is described by parametric equations, we compute the $x$ a

|

|

552

|

570

|

|

|

553

|

571

|

---

|

|

554

|

572

|

|

|

555

|

|

-##Laboratory session:

|

|

|

573

|

+## Laboratory session:

|

|

556

|

574

|

|

|

557

|

575

|

In the introduction to the topic of functions you saw that in mathematics and in some programming languages, a function cannot return more than one result. In this laboratory experience's exercises you will practice how to use reference variables to obtain various results from a function.

|

|

558

|

576

|

|

|

559

|

|

-###Exercise 1

|

|

|

577

|

+### Exercise 1

|

|

560

|

578

|

|

|

561

|

579

|

In this exercise you will study the difference between pass by value and pass by reference.

|

|

562

|

580

|

|

|

|

@@ -571,20 +589,55 @@ In this exercise you will study the difference between pass by value and pass by

|

|

571

|

589

|

|

|

572

|

590

|

|

|

573

|

591

|

**Figure 3.** Graph of a circle with radius 5 and center in the origin displayed by the program *PrettyPlot*.

|

|

574

|

|

-

|

|

|

592

|

+

|

|

575

|

593

|

---

|

|

576

|

594

|

|

|

577

|

595

|

3. Open the file `main.cpp` (in Sources). Study the `illustration` function and how to call it from the `main` function. Note that the variables `argValue` and `argRef`are initialized to 0 and that the function call for `illustration` makes a pass by value of `argValue` and a pass by reference of `argRef`. Also note that the corresponding parameters in `illustration` are assigned a value of 1.

|

|

578

|

596

|

|

|

|

597

|

+ void illustration(int paramValue, int ¶mRef) {

|

|

|

598

|

+ paramValue = 1;

|

|

|

599

|

+ paramRef = 1;

|

|

|

600

|

+ cout << endl << "The content of paramValue is: " << paramValue << endl

|

|

|

601

|

+ << "The content of paramRef is: " << paramRef << endl;

|

|

|

602

|

+ }

|

|

|

603

|

+

|

|

579

|

604

|

4. Execute the program and observe what is displayed in the window `Application Output`. Notice the difference between the content of the variables `argValue` and `argRef` despite the fact that both had the same initial value, and that `paramValue` and `paramRef` were assigned the same value. Explain why the content of `argValor` does not change, while the content of `argRef` changes from 0 to 1.

|

|

580

|

605

|

|

|

581

|

|

-###Exercise 2

|

|

|

606

|

+### Exercise 2

|

|

582

|

607

|

|

|

583

|

608

|

In this exercise you will practice the creation of an overloaded function.

|

|

584

|

609

|

|

|

585

|

610

|

**Instructions**

|

|

586

|

611

|

|

|

587

|

|

-1. Study the code in the `main()` function in the file `main.cpp`. The line `XYPlotWindow wCircleR5;` creates a `wCircleR5` object that will be the window where the graph will be drawn, in this case the graph of a circle of radius 5. In a similar way, the objects `wCircle` and `wButterfly` are created. Observe the `for` cycle. In this cycle a series of values for the angle $t$ is generated and the function `circle` is invoked, passing the value for $t$ and the references to $x$ and $y$. The `circle` function does not return a value, but using parameters by reference, it calculates the values for the coordinates $xCoord$ and $yCoord$ for the circle with center in the origin and radius 5, and allows the `main` function to have these values in the `x` , `y` variables.

|

|

|

612

|

+1. Study the code in the `main()` function in the file `main.cpp`.

|

|

|

613

|

+

|

|

|

614

|

+ XYPlotWindow wCircleR5;

|

|

|

615

|

+ XYPlotWindow wCircle;

|

|

|

616

|

+ XYPlotWindow wButterfly;

|

|

|

617

|

+

|

|

|

618

|

+ double r;

|

|

|

619

|

+ double y = 0.00;

|

|

|

620

|

+ double x = 0.00;

|

|

|

621

|

+ double increment = 0.01;

|

|

|

622

|

+ int argValue=0, argRef=0;

|

|

|

623

|

+

|

|

|

624

|

+ // invoke the function illustration to view the contents of variables

|

|

|

625

|

+ // by value and by reference

|

|

|

626

|

+

|

|

|

627

|

+ illustration(argValue,argRef);

|

|

|

628

|

+ cout << endl << "The content of argValue is: " << argValue << endl

|

|

|

629

|

+ << "The content of argRef is: " << argRef << endl;

|

|

|

630

|

+

|

|

|

631

|

+ // repeat for several values of the angle t

|

|

|

632

|

+ for (double t = 0; t < 16*M_PI; t = t + increment) {

|

|

|

633

|

+

|

|

|

634

|

+ // invoke circle with the angle t and reference variables x, y as arguments

|

|

|

635

|

+ circle(t,x,y);

|

|

|

636

|

+

|

|

|

637

|

+ // add the point (x,y) to the graph of the circle

|

|

|

638

|

+ wCircleR5.AddPointToGraph(x,y);

|

|

|

639

|

+

|

|

|

640

|

+ The line `XYPlotWindow wCircleR5;` creates a `wCircleR5` object that will be the window where the graph will be drawn, in this case the graph of a circle of radius 5. In a similar way, the objects `wCircle` and `wButterfly` are created. Observe the `for` cycle. In this cycle a series of values for the angle $t$ is generated and the function `circle` is invoked, passing the value for $t$ and the references to $x$ and $y$. The `circle` function does not return a value, but using parameters by reference, it calculates the values for the coordinates $xCoord$ and $yCoord$ for the circle with center in the origin and radius 5, and allows the `main` function to have these values in the `x` , `y` variables.

|

|

588

|

641

|

|

|

589

|

642

|

After the function call, each ordered pair $(x,y)$ is added to the circle’s graph by the member function `AddPointToGraph(x,y)`. After the cycle, the member function `Plot()` is invoked, which draws the points, and the member function `show()`, which displays the graph. The *members functions* are functions that allow use to work with and object’s data. Notice that each one of the member functions is written after `wCircleR5`, followed by a period. In an upcoming laboratory experience you will learn more about objects, and practice how to create them and invoke their method functions.

|

|

590

|

643

|

|

|

|

@@ -592,7 +645,7 @@ In this exercise you will practice the creation of an overloaded function.

|

|

592

|

645

|

|

|

593

|

646

|

2. Now you will create an overloaded function `circle` that receives as arguments the value of the angle $t$, the reference to the variables $x$ and $y$, and the value for the radius of the circle. Invoke the overloaded function `circle` that you just implemented from `main()` to calculate the values of the coordinates $x$ and $y$ for the circle with radius 15 and draw its graph. Graph the circle within the `wCircle` object. To do this, you must invoke the method functions `AddPointToGraph(x,y)`, `Plot` and `show` from `main()`. Remember that these should be preceded by `wCircle`, for example, `wCircle.show()`.

|

|

594

|

647

|

|

|

595

|

|

-###Exercise 3

|

|

|

648

|

+### Exercise 3

|

|

596

|

649

|

|

|

597

|

650

|

In this exercise you will implement another function to calculate the coordinates of the points in the graph of a curve.

|

|

598

|

651

|

|

|

|

@@ -600,19 +653,21 @@ In this exercise you will implement another function to calculate the coordinate

|

|

600

|

653

|

|

|

601

|

654

|

1. Now you will create a function to calculate the coordinates of the points of a graph that resembles a butterfly. The parametric equations for the coordinates of the points in the graph are given by:

|

|

602

|

655

|

|

|

603

|

|

-

|

|

604

|

656

|

$$x=5\cos(t) \left[ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t) \right]$$

|

|

|

657

|

+

|

|

605

|

658

|

$$y= 10\sin(t) \left[ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t) \right].$$

|

|

606

|

659

|

|

|

607

|

660

|

Observe that both expressions are almost the same, except that one starts with $5\cos(t)$ and the other with $10\sin(t)$. Instead of doing the calculation for $ \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t)$ twice, you can assign its value to another variable $q$ and calculate it as such:

|

|

608

|

661

|

|

|

609

|

662

|

$$q = \sin^2(1.2t) + \cos^3(6t)$$

|

|

|

663

|

+

|

|

610

|

664

|

$$x = 5 \cos(t)(q)$$

|

|

|

665

|

+

|

|

611

|

666

|

$$y = 10 \sin(t)(q).$$

|

|

612

|

667

|

|

|

613

|

668

|

2. Implement the function `butterfly` using the expressions above, invoke the function in `main()` and observe the resulting graph. It is supposed to look like a butterfly. This graph should have been obtained with a `XYPlotWindow` object called `wButterfly`, invoking method functions similar to how you did in Exercise 2 for the circle.

|

|

614

|

669

|

|

|

615

|

|

-In [3] you can find other parametric equations from other interesting curves.

|

|

|

670

|

+In [2] and [3] you can find other parametric equations from other interesting curves.

|

|

616

|

671

|

|

|

617

|

672

|

---

|

|

618

|

673

|

---

|

|

|

@@ -632,4 +687,4 @@ Use "Deliverables" in Moodle to hand in the file `main()` that contains the func

|

|

632

|

687

|

|

|

633

|

688

|

[2] http://paulbourke.net/geometry/butterfly/

|

|

634

|

689

|

|

|

635

|

|

-[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parametric_equation

|

|

|

690

|

+[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parametric_equation

|