|

|

10 년 전 | |

|---|---|---|

| UnitTests | 10 년 전 | |

| images | 10 년 전 | |

| resources | 10 년 전 | |

| Guia para el instructor.docx | 10 년 전 | |

| README.md | 10 년 전 | |

| Testing.html | 10 년 전 | |

| Testing.md | 10 년 전 | |

| Testing.pro | 10 년 전 | |

| functions.cpp | 10 년 전 | |

| functions.h | 10 년 전 | |

| images.qrc | 10 년 전 | |

| imagesTesting.zip | 10 년 전 | |

| labTesting.md | 10 년 전 | |

| main.cpp | 10 년 전 | |

| mainwindow.cpp | 10 년 전 | |

| mainwindow.h | 10 년 전 | |

| mainwindow.ui | 10 년 전 | |

| secondwindow.cpp | 10 년 전 | |

| secondwindow.h | 10 년 전 |

README.md

Pruebas y pruebas unitarias

Como habrás aprendido en experiencias de laboratorio anteriores, lograr que un programa compile es solo una pequeña parte de programar. El compilador se encargará de decirte si hubo errores de sintaxis, pero no podrá detectar errores en la lógica del programa. Es muy importante probar las funciones del programa para validar que producen los resultados correctos y esperados.

Una manera de hacer estas pruebas es “a mano”, esto es, corriendo el programa múltiples veces, ingresando valores representativos (por medio del teclado) y visualmente verificando que el programa devuelve los valores esperados. Otra forma más conveniente es implementar funciones dentro del programa cuyo propósito es verificar que otras funciones produzcan resultados correctos. En esta experiencia de laboratorio practicarás ambos métodos de verificación.

Objetivos:

- Validar el funcionamiento de varias funciones haciendo pruebas “a mano”.

- Crear pruebas unitarias para validar funciones, utilizando la función

assert

Pre-Lab:

Antes de llegar al laboratorio debes:

Haber repasado los conceptos básicos relacionados a pruebas y pruebas unitarias.

Haber repasado el uso de la función

assertpara hacer pruebas.Haber estudiado los conceptos e instrucciones para la sesión de laboratorio.

Haber tomado el quiz Pre-Lab que se encuentra en Moodle.

Haciendo pruebas a una función.

Cuando probamos la validez de una función debemos probar casos que activen los diversos resultados de la función.

Ejemplo 1: si fueras a validar una función esPar(unsigned int n) que determina si un entero positivo n es par, deberías hacer pruebas a la función tanto con números pares como números impares. Un conjunto adecuado de pruebas para dicha función podría ser:

| Prueba | Resultado esperado |

|---|---|

esPar(8) |

true |

esPar(7) |

false |

Ejemplo 2: Digamos que un amigo ha creado una función unsigned int rangoEdad(unsigned int edad) que se supone que devuelva 0 si la edad está entre 0 y 5 (inclusive), 1 si la edad está entre 6 y 18 inclusive, y 2 si la edad es mayor de 18. Una fuente común de errores en funciones como esta son los valores próximos a los límites de cada rango, por ejemplo, el número 5 se presta para error si el programador no usó una comparación correcta. Un conjunto adecuado de pruebas para la función rangoEdad sería:

| Prueba | Resultado esperado |

|---|---|

rangoEdad(5) |

0 |

rangoEdad(2) |

0 |

rangoEdad(6) |

1 |

rangoEdad(18) |

1 |

rangoEdad(17) |

1 |

rangoEdad(19) |

2 |

rangoEdad(25) |

2 |

La función assert

La función assert(bool expression) se puede utilizar como herramienta rudimentaria para validar de funciones. assert tiene un funcionamiento muy sencillo y poderoso. Si la expresión que colocamos entre los paréntesis de assert es cierta la función permite que el programa continúe con la próxima instrucción. De lo contrario, si la expresión que colocamos entre los paréntesis es falsa, la función assert hace que el programa termine e imprime un mensaje al terminal que informa al usuario sobre la instrucción de assert que falló.

Por ejemplo, el siguiente programa correrá de principio a fin sin problemas pues todos las expresiones incluidas en los paréntesis de los asserts evalúan a true.

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i = 10, j = 15;

assert(i == 10);

assert(j == i + 5);

assert(j != i);

assert( (j < i) == false);

cout << "Eso es todo, amigos!" << endl;

return 0;

}

Figura 1. Ejemplo de programa que pasa todas las pruebas de assert.

El siguiente programa no correrá hasta el final pues el segundo assert (assert(j == i);) contiene una expresión (j==i) que evalúa a false.

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i = 10, j = 15;

assert(i == 10);

assert(j == i);

assert(j != i);

assert( (j < i) == false);

cout << "Eso es todo, amigos!" << endl;

return 0;

}

Figura 2. Ejemplo de programa que no “pasa” una prueba de assert.

Al correr el pasado programa, en lugar de obtener la frase ”Eso es todo amigos!” en el terminal, obtendremos un mensaje como el siguiente:

Assertion failed: (j == i), function main, file ../programa01/main.cpp, line 8.

El programa no ejecuta más instrucciones después de la línea 8.

¿Cómo usar assert para validar funciones?

Digamos que deseas automatizar la validación de la función rangoEdad. Un forma de hacerlo es crear una función que llame a la función rangoEdad con diversos argumentos y verifique que lo devuelto concuerde con el resultado esperado. Si incluimos cada comparación entre lo devuelto por rangoEdad y el resultado esperado dentro de un assert, obtenemos una función que se ejecuta de principio a fin solo si todas las invocaciones devolvieron el resultado esperado.

void test_rangoEdad() {

assert(rangoEdad(5) == 0);

assert(rangoEdad(2) == 0);

assert(rangoEdad(6) == 1);

assert(rangoEdad(18) == 1);

assert(rangoEdad(17) == 1);

assert(rangoEdad(19) == 2);

assert(rangoEdad(25) == 2);

cout << "rangoEdad passed all tests!!!" << endl;

}

Figura 3. Ejemplo de una función para pruebas usando assert.

!INCLUDE “../../eip-diagnostic/testing/es/diag-testing-01.html”

!INCLUDE “../../eip-diagnostic/testing/es/diag-testing-02.html”

Sesión de laboratorio:

Ejercicio 1: Diseñar pruebas “a mano”

En este ejercicio practicarás cómo diseñar pruebas para validar funciones, utilizando solamente la descripción de la función y la interfaz gráfico que se usa para interactuar con la función.

El ejercicio NO requiere programación, solo requiere que entiendas la descripción de la función, y tu habilidad para diseñar pruebas. Este ejercicio y el Ejercicio 2 son una adaptación de la actividad descrita en [1].

Ejemplo 3. Supón que una amiga te provee un programa. Ella asegura que el programa resuelve el siguiente problema:

"dados tres enteros, despliega el valor máximo".

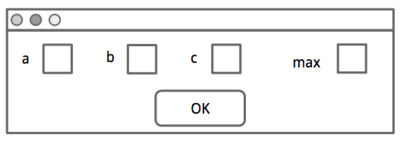

Supón que el programa tienen una interfaz como la siguiente:

Figura 4 - Interfaz de un programa para hallar el valor máximo entre tres enteros.

Podrías determinar si el programa provee resultados válidos sin analizar el código fuente. Por ejemplo, podrías intentar los siguientes casos:

- a = 4, b = 2, c = 1; resultado esperado: 4

- a = 3, b = 6, c = 2; resultado esperado: 6

- a = 1, b = 10, c = 100; resultado esperado: 100

Si alguno de estos tres casos no da el resultado esperado, el programa de tu amiga no funciona. Por otro lado, si los tres casos funcionan, entonces el programa tiene una probabilidad alta de estar correcto.

Funciones para validar

En este ejercicio estarás diseñando pruebas que validen varias versiones de las funciones que se describen abajo. Cada una de las funciones tiene cuatro versiones, “Alpha”, “Beta”, “Gamma” y “Delta”.

- 3 Sorts: una función que recibe tres “strings” y los ordena en orden lexicográfico (alfabético). Por ejemplo, dados

jirafa,zorra, ycoqui, los ordena como:coqui,jirafa, yzorra. Para simplificar el ejercicio, solo usaremos “strings” con letras minúsculas. La Figura 5 muestra la interfaz de esta función. Nota que hay un menú para seleccionar la versión implementada.

**Figura 5** - Interfaz de la función `3 Sorts`.

- Dice: cuando el usuario marca el botón

Roll them!, el programa genera dos enteros aleatorios entre 1 y 6. El programa informa la suma de los enteros aleatorios.

**Figura 6** - Interfaz de la función `Dice`.

- Rock, Paper, Scissors: cada uno de los jugadores entra su jugada y el programa informa quién ganó. La Figura 7 muestra las opciones en las que un objeto le gana a otro. La interfaz del juego se muestra en la Figura 8.

**Figura 7** - Formas de ganar en el juego "Piedra, papel y tijera".

**Figura 8** - Interfaz de la función `Rock, Paper, Scissors`.

Zulu time: Dada una hora en tiempo Zulu (Hora en el Meridiano de Greenwich) y la zona militar en la que el usuario desea saber la hora, el programa muestra la hora en esa zona. El formato para el dato de entrada es en formato de 23 horas

####, por ejemplo2212sería las 10:12 pm. Puedes encontrar la lista de zonas militares válidas en http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_military_time_zones. Lo que sigue son ejemplos de cómo deben ser los resultados del programa:- Dada hora Zulu 1230 y zona A (UTC+1), el resultado debe ser 1330.

- Dada hora Zulu 1230 y zona N (UTC-1), el resultado debe ser 1130.

- Puerto Rico está en la zona militar Q (UTC-4), por lo tanto, cuando es 1800 en hora Zulu, son las 1400 en Puerto Rico.

**Figura 9** - Interfaz de la función `Zulu time`.

Instrucciones

- Para cada una de las funciones descritas arriba, escribe en tu libreta las pruebas que harás para determinar la validez de cada implementación (Alpha, Beta, Gamma y Delta). Para cada función, piensa en los errores lógicos que el programador pudo haber cometido y escribe pruebas que determinen si se cometió ese error. Para cada prueba, escribe los valores que utilizarás y el resultado que esperas obtener.

Por ejemplo, puedes organizar tus respuestas en una tabla como la que sigue:

| 3 Sorts | | | | | | |---------|---------------------------|---------------------------|-----------|------------|------------| | Num | Prueba | Result Alpha | Res. Beta | Res. Gamma | Res. Delta | | 1 | “alce”, “coyote”, “zorro” | “alce”, “coyote”, “zorro” | …. | …. | | | 2 | “alce”, “zorro”, “coyote” | “zorro”, “alce”, “coyote” | …. | …. | | | …. | …. | …. | …. | …. | …. |

Figura 10 - Tabla para organizar los resultados de las pruebas.

Puedes ver ejemplos de cómo organizar tus resultados aquí y aquí.

Ejercicio 2: Hacer pruebas “a mano”

El proyecto testing implementa varias versiones de cada una de las cuatro funciones simples que se decribieron en el Ejercicio 1. Algunas o todas las implementaciones pueden estar incorrectas. Tu tarea es, usando las pruebas que diseñaste en el Ejercicio 1, probar las versiones de cada función para determinar cuáles de ellas, si alguna, están implementadas correctamente.

Este ejercicio NO requiere programación, debes hacer las pruebas sin mirar el código.

Instrucciones

Carga a Qt el proyecto

Testinghaciendo doble “click” en el archivoTesting.proen el directorioDocuments/eip/Testingde tu computadora. También puedes ir ahttp://bitbucket.org/eip-uprrp/testingpara descargar la carpetaTestinga tu computadora.Configura el proyecto y corre el programa. Verás una pantalla similar a la siguiente:

**Figura 11** - Ventana para seleccionar la función que se va a probar.

Selecciona el botón de

3 Sortsy obtendrás la interfaz de la Figura 5.La “Version Alpha” en la caja indica que estás corriendo la primera versión del algoritmo

3 Sorts. Usa las pruebas que escribiste en el Ejercicio 1 para validar la “Version Alpha”. Luego, haz lo mismo para las versiones Beta, Gamma y Delta. Escribe cuáles son las versiones correctas (si alguna) de la función y porqué. Recuerda que, para cada función, algunas o todas las implementaciones pueden estar incorrectas. Además, especifica cuáles pruebas te permitieron determinar las versiones que son incorrectas.

Ejercicio 3: Usar assert para realizar pruebas unitarias

Hacer pruebas “a mano” cada vez que corres un programa es una tarea que resulta “cansona” bien rápido. En los ejercicios anteriores lo hiciste para unas pocas funciones simples. ¡Imagínate hacer lo mismo para un programa complejo completo como un navegador o un procesador de palabras!

Las pruebas unitarias ayudan a los programadores a validar códigos y simplificar el proceso de depuración (“debugging”) a la vez que evitan la tarea tediosa de hacer pruebas a mano en cada ejecución.

Instrucciones:

En el menú de QtCreator, ve a

Buildy seleccionaClean Project "Testing". Luego ve aFiley seleccionaClose Project "Testing".Carga a QtCreator el proyecto

UnitTestshaciendo doble “click” en el archivoUnitTests.proen el directorioDocuments/eip/Testing/UnitTestsde tu computadora. Si descargaste el directorioTestinga tu computadora durante el ejercicio 2, el directorioUnitTestsestará bajo ese directorio.El proyecto solo contiene el archivo de código fuente

main.cpp. Este archivo contiene cuatro funciones:fact,isALetter,isValidTime, ygcd, cuyos resultados son solo parcialmente correctos.

Estudia la documentación de cada función (los comentarios que aparecen previo a cada función) para que comprendas la tarea que se espera que haga cada función.

Tu tarea es escribir pruebas unitarias para cada una de las funciones para identificar los resultados erróneos. ** No necesitas reescribir las funciones para corregirlas. **

Para la función fact se provee la función test_fact() como función de prueba unitaria. Si invocas esta función desde main, compilas y corres el programa debes obtener un mensaje como el siguiente:

`Assertion failed: (fact(2) == 2), function test_fact, file ../UnitTests/ main.cpp, line 69.`

Esto es suficiente para saber que la función fact NO está correctamente implementada.

Nota que, al fallar la prueba anterior, el programa no continuó su ejecución. Para poder probar el código que escribirás, comenta la invocación de

test_fact()enmain.Escribe una prueba unitaria llamada

test_isALetterpara la funciónisALetter. En la prueba unitaria escribe varias afirmaciones (“asserts”) para probar algunos datos de entrada y sus valores esperados (mira la funcióntest_factpara que te inspires). Invocatest_isALetterdesdemainy ejecuta tu programa. Si la funciónisALetterpasa las pruebas que escribiste, continúa escribiendo “asserts” y ejecutando tu programa hasta que alguno de losassertsfalle.Comenta la invocación de

test_isALetterenmainpara que puedas continuar con las otras funciones.Repite los pasos 5 y 6 paras las otras dos funciones,

isValidTimeygcd. Recuerda que debes llamar a cada una de las funciones de prueba unitaria desdemainpara que corran.

Entregas

Utiliza “Entrega 1” en Moodle para entregar la tabla con las pruebas que diseñaste en el Ejercicio 1 y que completaste en el Ejercicio 2 con los resultados de las pruebas de las funciones.

Utiliza “Entrega 2” en Moodle para entregar el archivo

main.cppque contiene las funcionestest_isALetter,test_isValidTime,test_gcdy sus invocaciones. Recuerda utilizar buenas prácticas de programación, incluir el nombre de los programadores y documentar tu programa.

Referencias

[1] http://nifty.stanford.edu/2005/TestMe/

Testing and Unit Testing

As you have learned in previous labs, getting a program to compile is only a minor part of programming. The compiler will tell you if there are syntactical errors, but it isn’t capable of detecting logical problems in your program. It’s very important to test the program’s functions to validate that they produce correct results.

These tests can be performed by hand, this is, running the program multiple times, providing representative inputs and visually checking that the program outputs correct results. A more convenient way is to implement functions in the program whose sole purpose is to validate that other functions are working correctly. In this lab you will be practicing both testing methods.

Objectives:

- Design tests to validate several programs “by-hand”, then use these tests to determine if the program works as expected.

- Create unit tests to validate functions, using the

assertfunction.

Pre-Lab:

Before you get to the laboratory you should have:

Reviewed the basic concepts related to testing and unit tests.

Reviewed how to use the

assertfunction to validate another function.Studied the concepts and instructions for this laboratory session.

Taken the Pre-Lab quiz available in Moodle.

Testing a function

When we test a function’s validity we should test cases that activate the various results the function could return.

Example 1: if you were to validate the function isEven(unsigned int n) that determines if a positive integer n is even, you should test the function using even and odd numbers. A set of tests for that function could be:

| Test | Expected Result |

|---|---|

isEven(8) |

true |

isEven(7) |

false |

Example 2: Suppose that a friend has created a function unsigned int ageRange(unsigned int age) that is supposed to return 0 if the age is between 0 and 5 (inclusive), 1 if the age is between 6 and 18 inclusive, and 2 if the age is above 18. A common source of errors in functions like this one are the values near to the limits of each range, for example, the number 5 can cause errors if the programmer did not use a correct comparison. One good set of tests for the ageRange function would be:

| Test | Expected Result |

|---|---|

ageRange(5) |

0 |

ageRange(2) |

0 |

ageRange(6) |

1 |

ageRange(18) |

1 |

ageRange(17) |

1 |

ageRange(19) |

2 |

ageRange(25) |

2 |

Assert Function:

The assert(bool expression) function can be used as a rudimentary tool to validate functions. assert has a very powerful yet simple functionality. If the expression that we place between the assert parenthesis is true, the function allows the program to continue onto the next instruction. Otherwise, if the expression we place between the parenthesis is false, the assert function causes the program to terminate and prints an error message on the terminal that informs the user about the assert instruction that failed.

For example, the following program will run from start to finish without problems since every expression included in the assert’s parentheses evaluates to true.

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i = 10, j = 15;

assert(i == 10);

assert(j == i + 5);

assert(j != i);

assert( (j < i) == false);

cout << "That's all, folks!" << endl;

return 0;

}

Figure 1. Example of a program that passes all of the assert tests.

The following program will not run to completion because the second assert (assert(j == i);) contains an expression (j==i) that evaluates to false.

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i = 10, j = 15;

assert(i == 10);

assert(j == i);

assert(j != i);

assert( (j < i) == false);

cout << "That's all, folks!" << endl;

return 0;

}

Figure 2. Example of a program that does not pass an assert test.

When the program is run, instead of getting the phrase ”That's all, folks!” in the terminal, we will obtain something like:

Assertion failed: (j == i), function main, file ../program01/main.cpp, line 8.

The program will not execute the remaining instructions after line 8.

How to use assert to validate functions?

Suppose that you want to automate the validation of the ageRange. One way to do it is by implementing and calling a function that calls the ageRange function with different arguments and verifies that each returned value is equal to the expected result. If the ageRange function returns a value that is not expected, the testing function aborts the program and reports the test that failed. The following illustrates a function to test the ageRange function. Observe that it consists of one assert per each of the tests we had listed earlier.

void test_ageRange() {

assert(ageRange(5) == 0);

assert(ageRange(2) == 0);

assert(ageRange(6) == 1);

assert(ageRange(18) == 1);

assert(ageRange(17) == 1);

assert(ageRange(19) == 2);

assert(ageRange(25) == 2);

cout << "ageRange passed all tests!!!" << endl;

}

Figure 3. Example of a test function using assert.

!INCLUDE “../../eip-diagnostic/testing/en/diag-testing-01.html”

!INCLUDE “../../eip-diagnostic/testing/en/diag-testing-02.html”

Laboratory Session:

Exercise 1: Designing tests by hand:

In this exercise you will practice how to design tests to validate functions, using only the function’s description and the graphical user interface that is used interact with the function.

The exercise DOES NOT require programming, it only requires that you understand the function’s description, and your ability to design tests. This exercise and Exercise 2 are an adaptation of the activity described in [1].

Example 3 Suppose that a friend provides you with a program. She makes sure the program solves the following problem:

"given three integers, it displays the max value".

Suppose that the program has an interface like the following:

Figure 4 - Interface for a program that finds the max value out of three integers.

You could determine if the program provides valid results without analyzing the source code. For example, you could try the following cases:

- a = 4, b = 2, c = 1; expected result: 4

- a = 3, b = 6, c = 2; expected result: 6

- a = 1, b = 10, c = 100; expected result: 100

If one of these three cases does not have the expected result, your friend’s program does not work. On the other hand, if the three cases work, then the program has a high probability of being correct.

Functions to validate

In this exercise you will be designing tests to validate various versions of the functions that are described below. Each one of the functions has four versions, “Alpha”, “Beta”, “Gamma” and “Delta”.

- 3 Sorts: a function that receives three strings and orders them in lexicographic (alphabetical) order. For example, given

giraffe,fox, andcoqui, it would order them as:coqui,fox, andgiraffe. To simplify the exercise, we will be using strings with lowercase letters. Figure 5 shows the function’s interface. Notice there is a menu to select the implemented version.

**Figure 5** - Interface for the `3 Sorts` function.

- Dice: when the user presses the

Roll them!button, the program generates two random integers between 1 and 6. The program informs the sum of the two random integers.

**Figure 6** - Interface for the `Dice` function.

- Rock, Paper, Scissors: each one of the players enters their play and the program informs who the winner is. Figure 7 shows the options where one object beats the other. The game’s interface is shown in Figure 8.

**Figure 7** - Ways to win in "Rock, paper, scissors".

**Figure 8** - Interface for the `Rock, Paper, Scissors` function.

Zulu time: Given a time in Zulu format (time at the Greenwich Meridian) and the military zone in which the user wants to know the time, the program shows the time in that zone. The format for the entry data is in the 24 hour format

####, for example2212would be 10:12pm. The list of valid military zones can be found in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_military_time_zones. The following are examples of some valid results:- Given Zulu time 1230 and zone A (UTC+1), the result should be 1330.

- Given Zulu time 1230 and zone N (UTC-1), the result should be 1130.

- Puerto Rico is in military zone Q (UTC-4), therefore, when its 1800 in Zulu time, it’s 1400 in Puerto Rico.

**Figure 9** - Interface for the `Zulu time` function.

Instructions

For each of the functions described above, write in your notebook the tests that you will do to determine the validity of each implementation (Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta). For each function, think of the logical errors that the programmer could have made and write tests that determine if these errors were made. For each test, write the values that you will use and the expected result.

For example, you could organize your answers in a table like the following:

| 3 Sorts | | | | | | |---------|---------------------------|---------------------------|-----------|------------|------------| | Num | Test | Alpha Result | Beta Result | Gamma Result | Delta Result | | 1 | “deer”, “coyote”, “fox” | “coyote”, “deer”, “fox” | …. | …. | | | 2 | “deer”, “fox”, “coyote” | “fox”, “deer”, “coyote” | …. | …. | | | …. | …. | …. | …. | …. | …. |

Figure 10 - Table to organize the test results.

You can see examples of how to organize your results here and here.

Exercise 2: Doing tests “by hand”

The testing project implements several versions of each of the four functions that were described in Exercise 1. Some or all of the implementations could be incorrect. Your task is, using the tests you designed in Exercise 1, to test the versions for each function to determine which of them, if any, are implemented correctly.

This exercise DOES NOT require programming, you should make the tests without looking at the code.

Instructions

Load the

Testingproject onto Qt by double clicking theTesting.profile in theDocuments/eip/Testingdirectory on your computer. You can also go tohttp://bitbucket.org/eip-uprrp/testingto downloaded theTestingfolder on your computer.Configure the project and run the program. You will see a window similar to the following:

**Figure 11** - Window to select the function that will be tested.

Select the button for

3 Sortsand you will obtain the interface in Figure 5.The “Alpha Version” in the box indicates that you’re running the first version of the

3 Sortsalgorithm. Use the tests that you wrote in Exercise 1 to validate the “Alpha Version”. Afterwards, do the same with the Beta, Gamma and Delta versions. Write down which are the correct versions of the function (if any), and why. Remember that, for each function, some or all of the implementations could be incorrect. Additionally, specify which tests allowed you to determine the incorrect versions.

Exercise 3: Using assert to make unit tests

Doing tests by hand each time you run a program is a tiresome task. In the previous exercises you did it for a few simple functions. Imagine doing the same for a complex program like a search engine or a word processor.

Unit tests help programmers validate code and simplify the process of debugging while avoiding having to do these tests by hand in each execution.

Instructions:

In the QtCreator menu, go to

Buildand selectClean Project "Testing". Then go toFileand selectClose Project "Testing".Load the

UnitTestsproject onto QtCreator by double clicking theUnitTests.profile in theDocuments/eip/Testingdirectory on your computer. If you downloaded theTestingdirectory in Exercise 2, theUnitTestsdirectory should be insideTesting.The project only contains the source code file

main.cpp. This file contains four functions:fact,isALetter,isValidTime, andgcd, whose results are only partially correct.Study the description of each function that appears as a comment before the function’s code to understand the task that the function is supposed to carry out.

Your task is to write unit tests for each of the functions to identify the erroneous results. You do not need to rewrite the functions to correct them.

For the

factfunction, atest_fact()is provided as a unit test function. If you invoke the function frommain, compile and run the program you should obtain a message like the following:Assertion failed: (fact(2) == 2), function test_fact, file ../UnitTests/ main.cpp, line 69.This is evidence enough to establish that the

factfunction is NOT correctly implemented.Notice that, by failing the previous test, the program did not continue its execution. To test the code you will write, comment the

test_fact()call inmain.Write a unit test called

test_isALetterfor theisALetterfunction. Write various asserts in the unit test to try some data and its expected values (use thetest_factfunction for inspiration). Invoketest_isALetterfrommainand execute your program. If theisALetterfunction passes the test you wrote, continue writing asserts and executing the program until one of them fails.Comment the

test_isALettercall inmainso you can continue with the other functions.Repeat the steps in 5 and 6 for the other two functions,

isValidTimeandgcd. Remember that you should call each of the unit test functions frommainfor them to run.

Deliverables

Use “Deliverables 1” in Moodle to hand in the table with the tests you designed in Exercise 1 and that you completed in Exercise 2 with the results from the function tests.

Use “Deliverables 2” in Moodle to hand in the

main.cppfile that contains thetest_isALetter,test_isValidTime,test_gcdfunctions and their calls. Remember to use good programming techniques, include the name of the programmers involved and document your program.